Transilvania IFF – Chirilov’s Recommendations

“Any film, regardless of its content, can become a political weapon, it depends on the context and the ability and interest of the person who instruments it to fit an agenda”, says Mihai Chirilov, the artistic director of the Transilvania Film Festival, in the already traditional interview of film recommendations during the ten days of the festival.

His statement bears witness to an era that finds us increasingly radicalised and separated from words. Stories are among our last resort to find the strength to not drift away from humanity forever. And from each other.

This year's image campaign is about love, and especially love of cinema. Which of this year's titles, apart from the usual suspect, Casablanca, advocates for a love like the one we see in the movies?

The campaign created by our partners at Leo Burnett works on several levels. It talks about love, but also about cinephile memory and a certain form of cinema obsession - sickening, yet benign. About films that stay with you, as a marker of your own personality or becoming. Or about the films that simply stay with you. Strangely, however, films of (or about) love are increasingly rare in today's cinema, as if such an endeavour would become an expression of auctorial weakness or frivolity unworthy of today's world where one must exercise social awarness or support the major causes of the day.

There are a few exceptions, however, such as Stillness in the Storm, a little Basque gem, part of this year’s Competition, a jazzy, minimalist yet sophisticated love story shot in black and white in a San Sebastian alien to the otherwise delightful picturesqueness of the place (parenthetically, it's a film that, for personal reasons, will stay with me forever as an entry in my own private diary). Or the Swedish 100 Seasons in the What's Up, Doc? competition, a tightrope hybrid where fiction uses documentary to provide therapeutic closure to an impossible love story. But if we're talking about those titles that stick, like Casablanca, this year's Transilvania IFF programme offers three other landmark classics that we can debate late into the night as to the fairness of tagging them today with the #lovestory tag: Breathless (from Godard's Close-up); Natural Born Killers (from Oliver Stone's Close-up); and Bertolucci's Last Tango in Paris, brought back into the limelight by a special screening of the restored version. The festival, let's not forget, is also a catalyst for providential encounters, where true love stories between TIFF-goers have happened over more than 20 editions. So, to paraphrase Humphrey Bogart's last line in Casablanca, Transilvania IFF can be “the beginning of a beautiful friendship”.

Five of the twelve films in competition are directed or co-directed by women. Was gender parity ever an issue, or did it just happen?

It just happened - and I think it's for the best. It seems excessive to me to regulate an artistic endeavour using criteria that circumvent quality and talent. I know, for example, of the existence of an almost accountancy manifesto from last decade, 50/50/2020, which promoted gender parity by 2020 and was opportunistically endorsed by dozens of festivals. I didn't have the inquisitional curiosity to check if their mission was accomplished (something tells me it wasn't), but someone was careful to triumphantly signal to me that, exactly in 2020, Transilvania IFF's competition was ticking off with flying colours in this respect. I didn't take it as a victory, it just happened that way. It's better when things like this happen organically, without an agenda. Besides, at least two female directors asked me at the time if their place in the competition was due to the new “directive” or artistic merit. It's easy to imagine the answer they would have liked to hear, and once again I had proof of how a seemingly laudable initiative can erode personal pride and confidence in one's own worth.

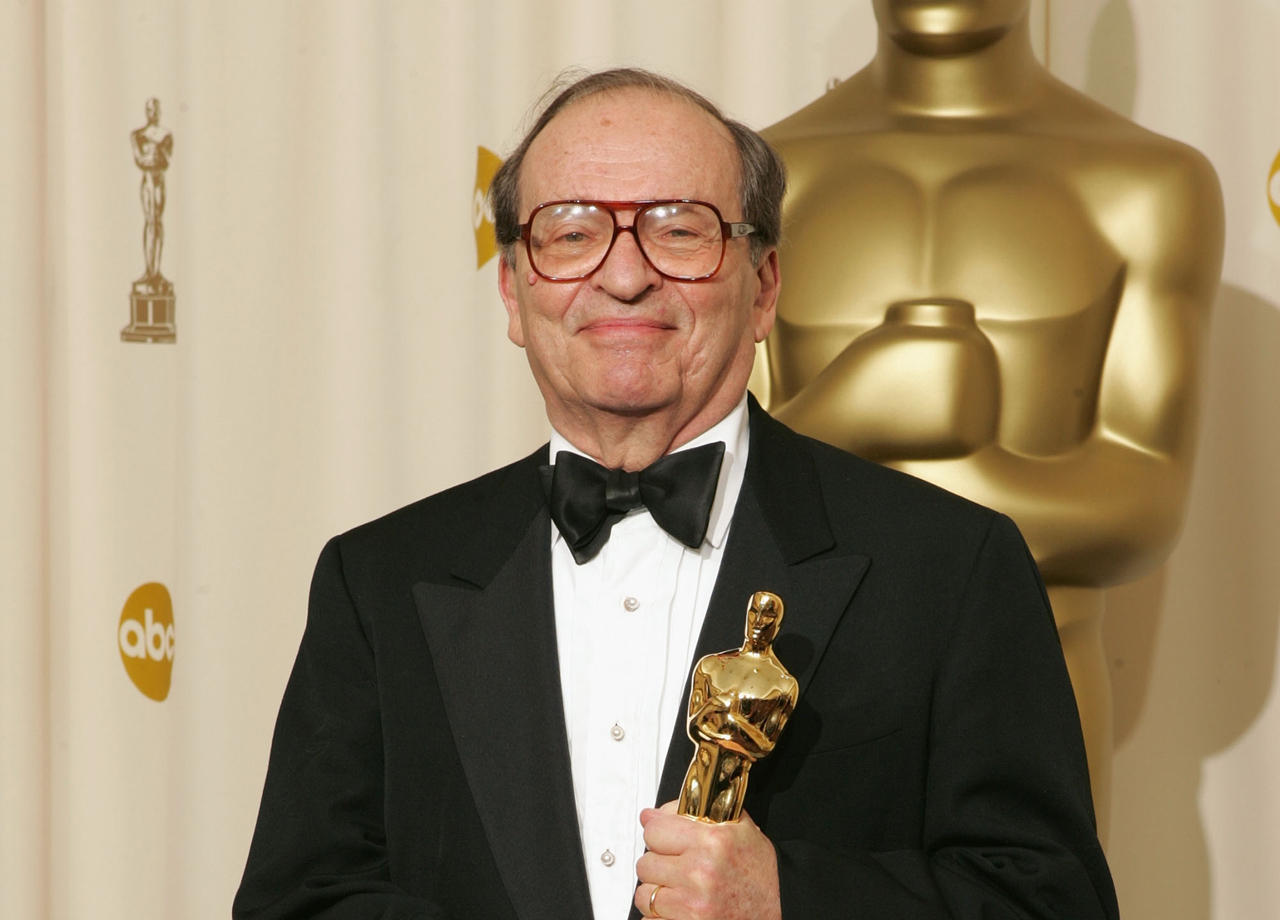

It's obvious why we have a Jean-Luc Godard close-up, but why the Sidney Lumet close-up now, before next year's centenary? How did the idea come about?

To be honest, I didn't know Sidney Lumet's centenary was next year. The idea of doing it this year came to me once I heard about the retrospective assembled last October by the Lumière Festival in Lyon, organised by Thierry Fremaux. Lumet is one of my favourite filmmakers, and most of the essential films in his filmography became available basically overnight in restored copies (from 12 Angry Men to Dog Day Afternoon to the cult-classic Network, still terribly topical - especially today). Why put off until tomorrow what I can do today? Besides, I already had another centenary idea in mind for 2024.

Although there are filmmakers highlighted outside the big retrospectives (Oliver Stone and György Fehér, for example), the 3x3 section is missing. Will it return in the future or is this a permanent change? How important is it for a big festival to bring something new every year?

The 3x3 mini-retrospective section has been a constant in Transilvania IFF's programme since the first edition. It's a sort of compressed section that either reveals filmmakers who have managed to make a name for themselves in a very short time, or established filmmakers who are still active and whose career we highlight through three key milestones from their beginnings to present day, or filmmakers who are no longer with us but who deserve to be discovered by a generation that is not familiar with their work. We won't give up on the 3x3 so easily, but we're not stuck obtusely in our own programme grid either - which is why we decided to temporarily suspend the section this year purely because we already had three auteur retrospectives (Godard, Lumet and Oliver Stone). Otherwise yes, it's important for festival to reinvent itself and come up with new things from one edition to the next - all the more so in a world that already seems programmed to change phones every couple of years to better versions.

While we usually have a country focus, this year Nordic Focus brings no less than five countries to the limelight. How challenging was the selection process and what shouldn't we miss?

The challenge was to see more films and find those particularities specific to the five countries (Sweden, Iceland, Denmark, Finland and Norway) that we otherwise tend to artificially group under one Nordic umbrella. My programme colleague Crăița Nanu managed this consistent and extremely varied selection admirably, doubling the lot of recent films with a collectible “truffle” from each country's golden archive. Not to be missed is the Swedish What a Fantastic Machine, a compulsive collage of clips retracing the history of Image (from the first photo ever taken to today's viral TikTok reels); the Danish The Cake Dynasty, a calorie bomb of political incorrectness; the unconventional Norwegian biopic Munch, where the famous artist is played by an actress and three actors (one of whom stars in the fragment set in contemporary Berlin); the black-and-white Icelandic black comedy Driving Mum; and Finland's Compartment No. 6, awarded the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes in 2022. As for archival gems, Lars von Trier's graduation film, Images of Liberation, is a must-see, and Iceland's Murder Story - a Bunuelian oddity for adventurous cinephiles.

At the press conference, you said that Romanian cinema is not at its best. What does the Romanian Film Days selection include this year and what would Romanian cinema need to get back to getting international recognition?

There were around 50 feature films submitted for the Romanian Film Days, of which less than half were finally selected. Record number of applicants - probably not something recurring in the years to come. I felt like I was stuck in traffic, in the deafening noise of honking horns. The general feeling of chaos, a meltdown of ideas. Some were good, even very good, but poorly executed or too well-behaved, rarely fulfilled. There are the obligatory returns to the communist past, which I find welcome - the topic is far from exhausted and justly represented in cinema. There are films that opportunistically latch on to trendy causes or themes, but don't always manage to score in other categories. There is an increasingly visible flirtation with the conventions of the blockbuster, but here too the outcome is not guaranteed. I think it is precisely this pressure of international recognition that is damaging, because it imprints on filmmakers a heightened insecurity about the topics that they have to tackle in order to find instant funding and validation. The international market is more unpredictable than ever. There are so many variables in this equation that the only solution is to really believe in the film you want to make. The rest is a lottery.

This year, films from Ukraine and Russia are missing from the selection. Would you say that this is a politically charged selection?

Films are missing not only from Russia and Ukraine, but also from many other countries that I won't list here. The fact that last year it was the other way around does not mean that the selection was intended to be politically charged. Some saw it that way. Personally, I avoid such positioning. They only damage the discourse about cinema and divert attention to another kind of clash of ideas equivalent to an armed duel. On the other hand, what is a political film today when even a harmless cat video on Instagram can become a pretext for bullying and segregation? Any film, regardless of its content, can become a political weapon, depending on the context and the skill and interest of the one instrumentalizing it to suit an agenda. I find it sad when an otherwise brilliant film ends up being talked about only in convenient hashtags. Probably if I were a PR & marketing manager, I would think differently.

Of all festival events, which one are you looking forward to?

“Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine”. As an avid gin collector and consumer that I am, I can't wait to hear this famous line on the screen in Piața Unirii.

Finally, what are your favourite films of the Transilvania IFF.22 selection?

In random order, and with favourite scenes: Manticore, probably my absolute favourite of the whole festival, fascinating and bitterly uncomfortable (big like Carlos Vermut); the choreography of family relationships and the cynical humour of Family Time and Charcoal; the jubilant, safety-net-less, sexually explicit madness of Rotting in the Sun, where Cioran becomes beach reading; The Critic, the documentary about Carlos Boyero, the provocative and uncomfortable film critic Almodovar wanted to cancel; The Coffee Table, whose cute diminutive in the Romanian title shouldn't fool you, on the contrary; Matias Bize's The Punishment, a one-shot film presenting the most heart-breaking, risky and yet true discourse on motherhood; the stupefyingly anguished ending of Rule 34 and the one of I Have Electric Dreams - simply perfect!; the Carverian mood in the stories in Smoke Sauna Sisterhood; the directorial masterclass in the claustrophobic thriller Upon Entry; the unique and spectacular documentary Knit's Island, filmed in a survival video game (big wow!); and last but not least, the stories in this year's surprise film, MMXX, a veritable pandemic pandemonium that Cristi Puiu had the daring inspiration to film in the heat of the darkest period in recent history.